In the small west-central Saskatchewan town where I grew up, “ethnic food” meant perogies (and, to be honest, I didn’t actually see one until I was 12).

Times have changed, and so has rural Saskatchewan.

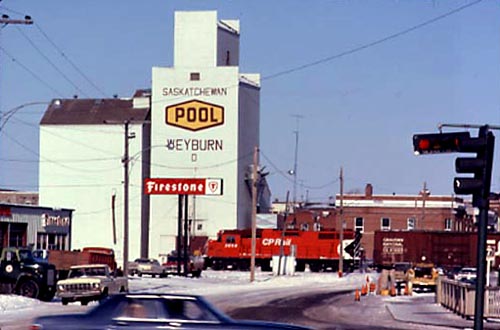

Never mind perogies, I can buy sushi at the Weyburn co-op.

New People

Between jobs in the Bakken oilfield, new construction work, and the service sector employment that comes with having more people around, Weyburn (a city of 10,000 people) is suddenly a magnet for people from all over the globe. My son took swimming lessons with a sweet little girl from Nigeria. His good friend from day care is Filipino, and the girl at his piano lesson introduced herself with, “my mom just bought me this new sparkly shirt in India.”

If we lived in Winnipeg, we wouldn’t have noticed any of this. But it’s a long way from Winnipeg to Weyburn (literally — five and a half hours), and this sort of cultural diversity is still new and exciting here.

Within 10 miles of our farm, women from Ecuador, Britain and the Philippines have married local farmers and settled in to the community.

When I moved here 10 years ago, you certainly couldn’t wander into the Weyburn library and check out a Ukrainian language book. Now, there’s a whole shelf of them.

Since I’ve moved here, almost every fast food restaurant in Weyburn has tapped into the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. It’s perfectly normal to walk into the McDonalds and hear three people behind the counter having a conversation in a language you’ve never heard before.

I went to high school in a town too small to have its own French teacher. In an optimistic attempt to broaden my horizons, my mother helpfully arranged for me to take French by correspondence (that is, she forced me to do it, using vicious threats). I still have nightmares where I’m mumbling “je suis, tu is est” into a squeaky tape recorder, so I could mail my homework cassette back to the instructor in Regina. It’s probably too late for me now (especially after that correspondence course), but I could probably find a real live person in Weyburn who would speak to me in French.

When I heard that the Weyburn Dairy Queen hired a handful of people from Mexico, I tried out my beginner-style Spanish the very next time I ordered a hot fudge sundae. The woman behind the counter didn’t understand what I was saying. By the time she figured out what I was up to, I was shouting ‘buenos dias’ at top volume. She got me to stop by telling me she was actually from the Philippines.

It’s a small world

The world is smaller now. Small enough that Weyburn can easily be part of it.

When my ancestors moved to the Prairies, they brought their food and customs along, but they left their homeland and friends behind, often for good. When my great, great grandmother left Norway, she knew she would never go back. There would be letters sent back and forth on boats, but she would never hear her brother’s voice again. She would hear news of Norway, but more than likely the only Norwegian language writing she’d see again would be in the books she carried with her.

By the time my great grandparents moved here from Newcastle, an ocean crossing wasn’t necessarily a one-way trip. Matthew and Sarah managed one trip back to Britain, on a slow boat. This trip was a momentous occasion — we still have the documents they saved carefully.

These days, my immigrant friend with a fast food job can fly home to Guadalajara at least once a year to visit his girlfriend, and still set some cash aside. And when he’s not back home, he’s got email, a low-cost long-distance phone card and Skype. He’s probably spending more time talking to his girlfriend than he did when he lived in Mexico. He can read the Guadalajara news on-line every morning. There’s even a website that lets him keep up to date with the telenovelas his friends at home are watching on TV.

The future

Oil booms come and go. It seems pretty likely that one day, when things slow down again, some of our new

The days when the local co-op would put the Tostitos salsa next to the China Lily soy sauce and label the aisle “ethnic foods” are over. Our children won’t have to find out about the rest of the world by hand-writing a letter to a pen pal they’d never see in real life then waiting at the post office for six weeks for a reply.

Immigration was the history of rural communities. Now it’s the present again. And the future. A world so interconnected that Weyburn can be part of the mesh will never fly apart.

___

Leeann Minogue is a Saskatchewan-based writer.

Follow us on Twitter @spectatortrib