He could have castigated his readers for caring so little about the plight of the poor and hungry. He could have lambasted government policy for failing to redress widespread famine and homelessness. Instead, he suggested they sell their sons and daughters as meat to wealthy nobleman and ladies. In so doing, Jonathan Swift did more in 1729 to draw attention to the plight of Irish peasants than any editorial could have done—and he did it using satire.

Swift was by no means the first to employ this literary genre. Romans had already turned it into an artform nearly 2,000 years earlier. There’s even evidence suggesting Ancient Egyptians were taking the piss 2,000 years before that.

Think about that for a moment: for over 4,000 years, humans—of every creed, colour, locality and ethnicity—have been using wit to peacefully protest social ills and the excesses of the elites; employing irony, sarcasm, analogy, and a host of other literary devices to cleverly critique monarchs and moguls, governments and gods.

That urge to speak truth to power—to call bullshit, even offend—might just be at the heart of what it means to be a human. At the very least, satire marvelously displays the heights to which the human intellect can soar—and how saying one thing but meaning another can do more to raise awareness, even bring about change than simply saying what we mean.

The Ancient Athenians understood the importance of free speech. The Ancient Romans, too. England enshrined it for parliamentarians in 1689. The French went so far as to affirm it as an inalienable right 100 years later. Though simply being allowed to express oneself freely does not quite capture the full essence and scope of it: people must be free to seek information and ideas, to receive them and to disseminate them—freely, without interference and without reprisal.

Tragically, throughout human history there have been those who have steadfastly opposed the freedom of speech, who have stamped out—violently, fatally—the dissemination of dissent, who have recoiled in horror and lashed out with a vengeance at the spread of differing opinions and new ideas. At every juncture and with every attempt those individuals, organizations, governments, and religions have always been met not with silence but with more words and louder voices.

To silence speech is to snuff out humanity itself. Try as some might, they will not succeed. Blood has been spilled before, bodies burned at stakes. Yet the voices remain, the ideas persist. And it is precisely those ideas that are met with greatest of hostilities we ought to discuss the loudest. Thank goodness we did, and we do: where would we be without the ideas of Kepler and Kant; Darwin and Descartes; Milton and Mill; Locke and Rousseau; Galileo and Copernicus? At one time, all of them were silenced—by the Roman Catholic Church—for offending the faithful and blaspheming their faith. Hilarious.

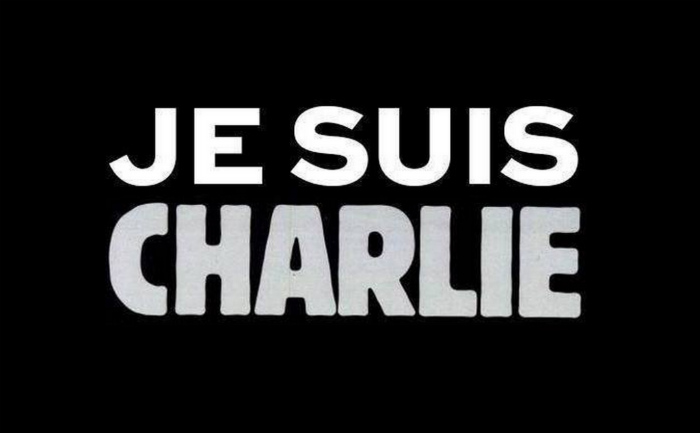

While few would argue the works published by Charlie Hebdo rivalled those of such thinkers, that they publish them (often about Islam) is no less important. Indeed, however crass some might have found their methods, however blunt the instrument of their criticism, there is much about Islam, as there was about Catholicism, to criticize. Indeed, ideas that prefer faith to reason, outlaw dissent, demand unthinking fealty, manufacture differences to instigate discord and hatred, promote misogyny and homophobia, and encourage acts of murder be committed in their name must surely be held up for public scrutiny if not outright humiliation. And if they offend? So what?

That is not to say free speech is without limits. There is a difference, though, between yelling “fire” in a crowded theatre and suggesting there is no God, or that one’s articles of faith are utterly ridiculous, without scientific or moral merit, anathema to humanity, truly deserving of disrespect.

It is impossible to offend a belief. Ideas, even religions, don’t have feelings. People do, though; and people tend to hold beliefs about all sorts of things, including the existence of god. Those people are often harmless. Mercifully, their religiosity is mostly benign. Sometimes, sadly, however, we witness malignant forms of such zealotry that test our resolve, and shake the very foundations of our society. What better way to respond to such a cancer than with that most human form of medicine: laughter.