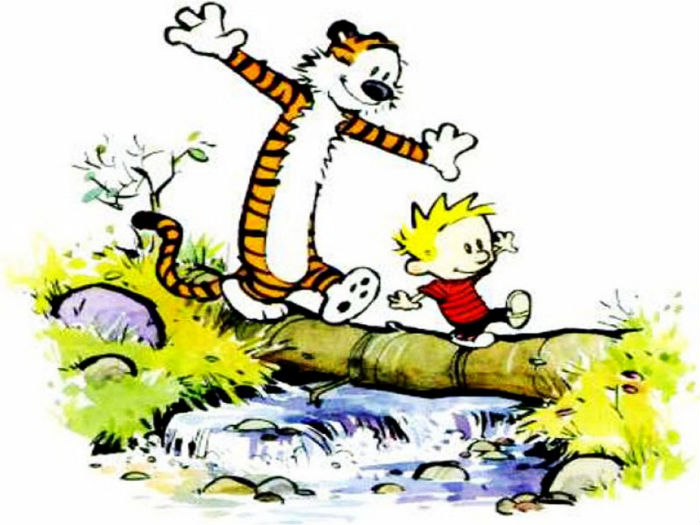

I remember my first experience with Calvin and Hobbes vividly.

We were visiting my great aunt and uncle in Calgary. They were marvelous people but there wasn’t much for a nine or ten year old to do. Until I found the first collection of Calvin and Hobbes on their bookshelf. Over the week or so we stayed with them, I read and re-read that collection daily. I had seen comic strips before but never something like this. I was hooked and I’m still hooked today, even though the strip ended its ten year run in 1995.

Since then, Bill Watterson’s creation has continued to be a fan favourite. At its peak, it was featured in more than 2,400 newspapers around the world with the reprints continuing to run even today. The collected editions are still hot sellers on book store shelves thanks to generations grew up with the cartoon are now introducing it to their kids. And all without the support of any kind of merchandising or licensing.

But why is it so popular?

That question is at the core of the documentary Dear Mr. Watterson: An Exploration of Calvin & Hobbes. Directed by Joel Allen Schroeder, this Kickstarter funded passion project is an attempt to understand why Calvin and Hobbes achieved the popularity and lasting success it has.

What it isn’t is an attempt to track down Bill Watterson, a noted recluse who shies away from the public eye and jam a camera in his face. Dan Piraro, creator of the cartoon Bizzaro and an interviewee for the documentary, describes Watterson as, “the sasquatch of cartoonists.” Essentially, he’s hard to find outside of a few grainy photos. And contacting Watterson isn’t really the point of the film. It’s about the impact of his work and any examination of the man behind it is only part of the bigger picture. They do go to his hometown to find out where the world of Calvin and Hobbes was birthed from. As the director/narrator notes, you can immediately see the environment that inspired the background the cartoon is set against.

There’s also a lot of discussion of his decisions on the licensing and merchandising of his work. While this is in complete opposition to the standard model of American cartoons, Watterson did little or no merchandising for his creation, nor did he license it. The only authorised merchandise is the collected editions of the strips and a couple of calendars.

Amongst the peers of Watterson’s that appear in the film are Berkeley Breathed (Bloom County, Opus) and the widow of the late Charles Schultz (Peanuts). They speak about his decision and the licensing choices made with the cartoons they’re associated with. Popular strips like Peanuts, Bloom County, Garfield, and Dilbert have all been merchandised, licensed, and thoroughly monetized to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions. Popular cartoons are big business. Watterson chose a different route, keeping Calvin and Hobbes in its purest form of consumption. The syndicate he works with, and technically owns the licensing rights to his work, has honored that though one can help but wonder if there will be a barrage of toys, t-shirts, video games, TV shows, and more after Watterson passes away.

The crazy thing about Calvin and Hobbes is that it is still socially relevant today and is not dated like many of its contemporaries. Calvin and Hobbes spend much of their time talking about high concept social, philosophical, and political ideas as well as delving into Calvin’s vast imagination but little or no time talking about the contemporary pop culture of the era the strips were written in (1985 to 1995). What pop culture there is exists only in the world of the strip. The common reference point it trades on is being a six year old, nothing more and nothing less.

The documentary concludes that the decision to not participate in the vast monetization machine that is still trying to drag Calvin and Hobbes into its clutches is a huge part of the reason why the strip endures. Its fans remember it fondly and have noted had that memory polluted by crass marketing. You can read it and feel like a kid again almost instantly.

The broad yet brilliant appeal of a strip that persists almost 20 years after its 10-year run ended is why Dear Mr. Watterson is necessary. This documentary does a great job examining the legacy of what is arguably the greatest and most impactful cartoon ever created, capturing it as the bar all cartoons that have come after it will be judged by. Calvin & Hobbes is, as said in the documentary, the last truly great newspaper comic strip.

And now I’m going to read the collected editions to my kids to make sure that legacy continues.